The bedrock of the corporate international tax framework is all set to change from 2023. As part of the reforms introduced under BEPS 2.0, the Inclusive Framework (IF) members agreed to a minimum tax of 15% on worldwide profits earned by Multinational Enterprises (MNEs). While the work was carried out to address tax challenges brought about by the so-called digital economy, the impetus is the mitigation of tax competition that has prompted a ‘race to the bottom’ on corporate tax rates in turn putting a strain on tax revenues.

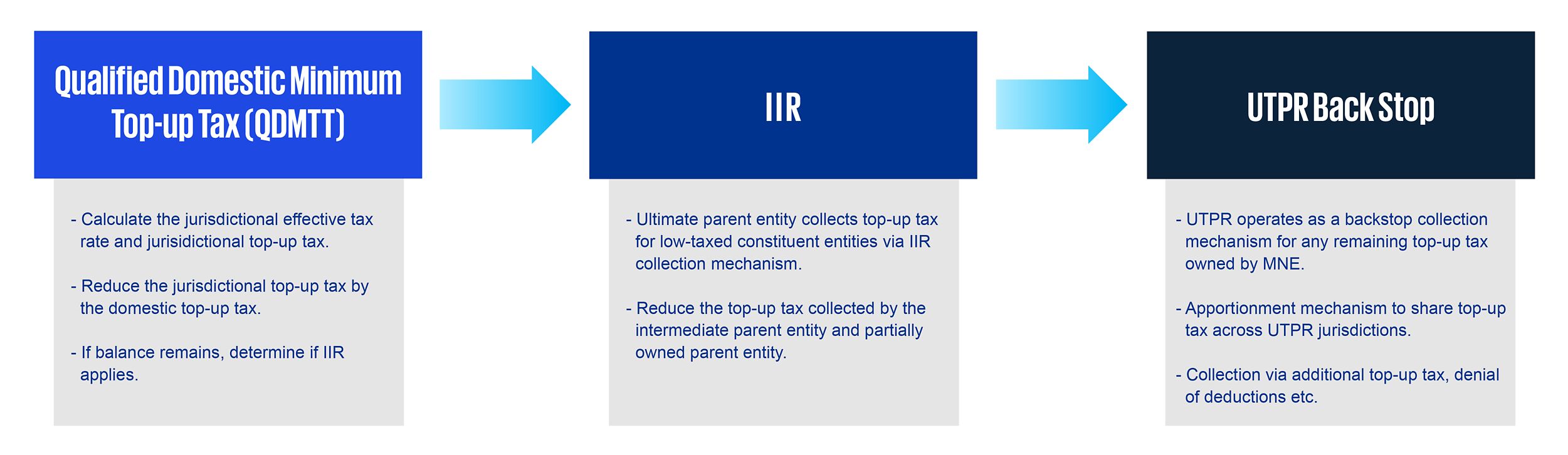

The Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) Rules that form part of Pillar II lay down the framework for ensuring the collection of minimum taxation by deploying an interlocking mechanism comprising the income inclusion rule (IIR) and the undertaxed profits rule (UTPR). The IRR imposes a top-up tax on the ultimate parent entity of a low-taxed subsidiary, while the UTPR is an adjustment that acts as a backstop in cases where the IIR fails to achieve the minimum corporate tax. Rules ensure that the relevant income is subject to at least 15% tax somewhere. For this reason, several jurisdictions are opting to reduce or eliminate tax revenue leakages by introducing a domestic top-up tax, thus ensuring that in-scope entities resident in their jurisdiction are subject to minimum corporate taxation therein.

We set out an overview of how the GloBE Rules work in the figure below:

Pillar II also includes a Subject-to-Tax rule which is a built-in double tax treaty rule to be adopted through a multilateral convention. This rule is an important compromise for developing nations given that it gives a Contracting State the right to withhold tax on certain types of related party transactions of a passive nature where the payments are not subject to a minimum tax rate of 9% in the recipient jurisdiction.

The EU issued a proposed minimum corporate tax Directive the day after the OECD published the Model Rules in December 2021. The draft Directive comprises the GloBE rules (not the Subject-to-Tax rule because this should be a matter for bilateral tax treaties) and closely follows the OECD Model GloBE Rules. It extends the scope to domestic groups so as to ensure alignment with the EU’s fundamental freedoms. The application of the Directive is expected to largely align itself with the OECD Commentary.

MNEs would need to allocate resources to ensure correct and complete reporting given that the Directive unavoidably increases their administrative burden to ensure compliance. In order to mitigate such risks, it would be prudent for such MNEs to undertake a high-level evaluation of the applicability of the Directive provisions, options and carve-outs to assess its impact in light of the MNE’s obtaining standing. It is also worth identifying potential sources for collating information and ironing out any issues with collecting the data. Tax teams and accounting teams would be required to work together since much of such information is based on accounting data and principles, particularly in relation to deferred tax.

The EU intends to adhere to the G20/OECD’s timeline by proposing transposition of the Directive by each Member State by 2024 for the IIR and by 2025 for the UTPR. Given the reluctance of the US Congress to adopt Pillar II and the proposed modification to align the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) rules, along with the uncertainty at ECOFIN over the adoption of Pillar II, this proposed implementation timeline remains unpredictable at best.

As part of the compromise sought amongst Member States, a derogation was provided for allowing Member States that host twelve or less Ultimate Parent Entities (UPEs) an option to defer the application of the GloBE rules by 6 years. Malta is expected to elect for the deferral to allow for a longer transition time meaning that local UPEs will start applying the rules to fiscal years beginning as from 31 December 2029. This said, an MNE would still need to assess the impact of other jurisdictions’ UTPR adjustment allocated to Malta. It would be prudent for each MNE to assess the impact of said UTPR on its financial and cashflow position in the light of such delayed application of the rules.

In order to ensure alignment of its current tax system with developing international tax rules, Malta’s Finance Minister has announced that work is undergoing to reassess and reformulate the mechanics of the tax system, including a migration from the current imputation system to a more classical system. The ongoing discussions also explore the co-existence of different permutations in respect of incentives and shareholder tax refunds in an attempt to ensure that the tax system, while keeping up with the times, remains competitive and sustainable, with limited ripple effects on out-of-scope taxpayers.