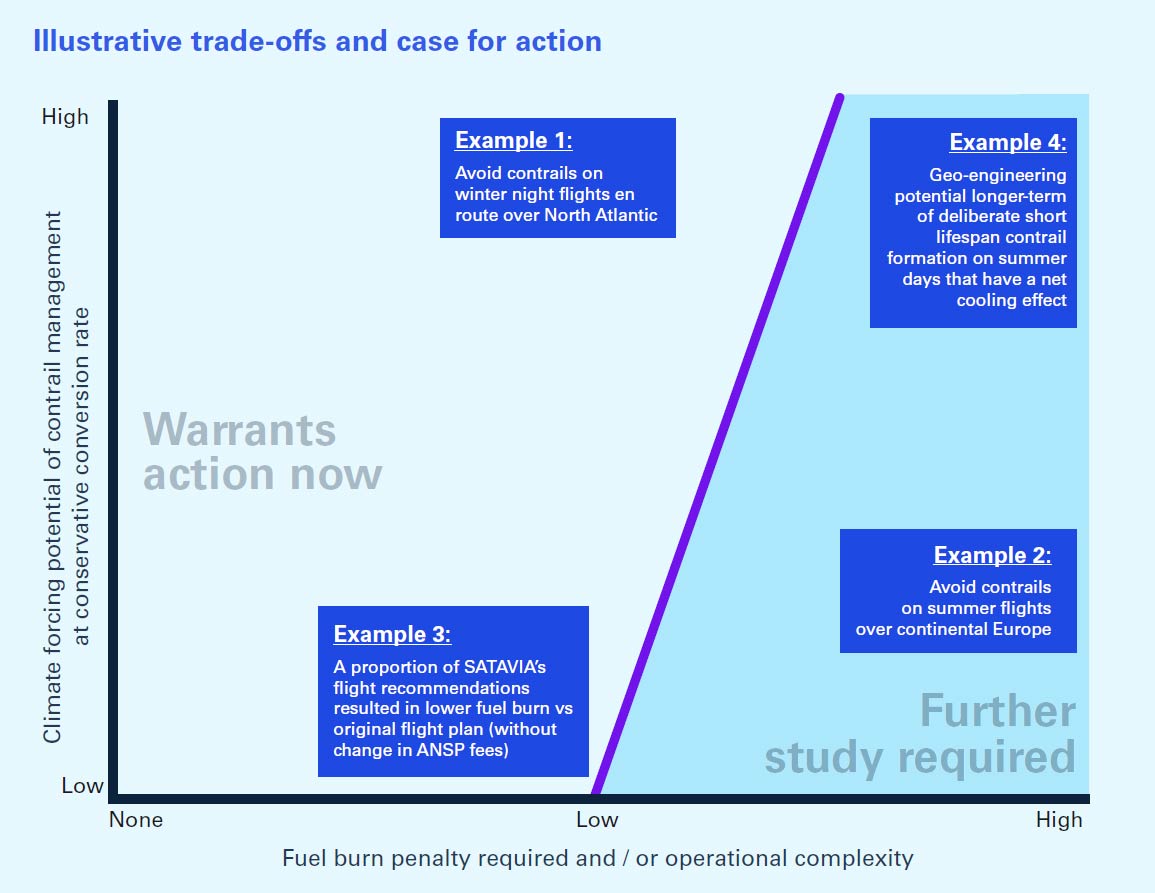

Not only is the contrail impact material under the more conservative assumption, but the most warming of contrails could be solved for now. Unlike in-flight emissions from fossil fuels, which require massive evolution in replacement technologies such as hydrogen, electric, and scaling of energy-intensive Sustainable Aviation Fuels, contrails can be addressed with today’s technology, offering the sector a golden opportunity for genuine green proactivity that goes far beyond the tokenism it is often accused of.

And with the EU ETS requiring non-CO2 impact reporting from 2025, airlines with EU route exposure have every reason to grasp the nettle. Mitigating contrail impact is relatively straightforward, relative that is, compared to the other tools at aviation’s disposal like air space redesign, new propulsion certification, or scaling new fuels supply.

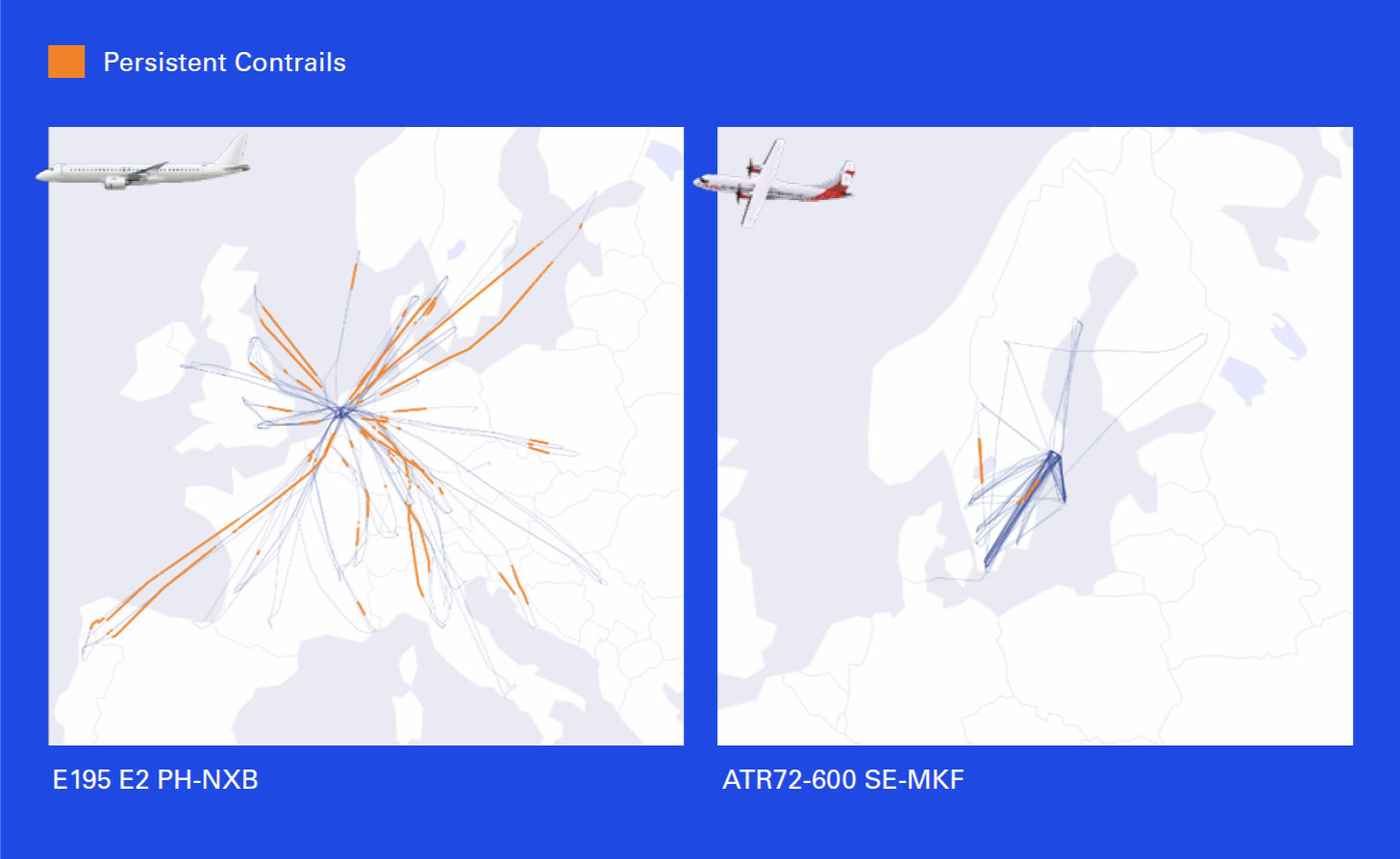

Since contrails are far more likely to form under particular atmospheric conditions (namely pockets of higher levels of moisture and lower temperatures), small adjustments in flight altitudes can avoid such conditions.

This need not be as massive an undertaking as it sounds, since research suggests that ~80% of the total contrail warming impact is caused by only ~2% of flights, with longhaul and night flights being the main concern.6

Whilst flights targeted for mitigation may face a fuel burn penalty for amending their flight routes, it is likely to be trivial – 2% according to a recent trial by Google and American Airlines,7 and no more than 0.5%, according to Ian Poll, Royal Aeronautical Society Past President and Emeritus Professor of Aerospace Engineering at Cranfield University, a figure corroborated by real-world adjustments recommended by contrail modelling specialist SATAVIA in trials backed by the European Space Agency with over 10 airlines, which has found on average that a fuel burn difference equating to ~100kg CO2 is necessary to mitigate 52T CO2e.

Keep in mind this is a per adjusted flight route – since even many long-haul flights will not create contrails on a given day, an airline-wide fuel burn penalty is likely to be more in the region of 0.01% of airline fuel total.8

At this level, any such penalty would be significantly less than the typical fuel excess already burned routinely by airlines pursuing maximally profitable operations, which depend on a range of factors including flight time, air traffic management charges, crew hours, aircraft rotation requirements, air traffic congestion time slots, etc.